To ensure that all people have opportunities to live, learn and work in public places, in recent years there has been an increased effort to create sensory-friendly environments. Through funding provided via the American Library Association’s Libraries Transforming Communities: Accessible Small and Rural Libraries (LTC) grant, small and rural libraries have made incredible strides in the design of sensory-friendly programs, collections, and spaces. In this blog post, we share what some LTC grantees are doing to become more accessible to community members with sensory sensitivities.

A particular focus of our discussion is programs. Through the process of studying and hosting sensory-friendly programs, we’ve learned that designing and implementing these is easier than you might think! Our research and our practice indicates that creating a successful sensory-friendly program comes down to four key considerations:

- Think in advance about ways a program could be overstimulating (and how it could be modified to be less so);

- Build in transition times;

- Strike a balance between designing programs specifically for sensory-sensitive individuals and making all programs accessible to these patrons; and

- Ensure that all patrons are welcome (including adults!).

In what follows, we provide examples of how LTC grantees are putting these key ideas into practice.

Making Existing Programs (and Spaces!) More Accessible

With a few adjustments, many existing library programs can be made more accessible to individuals with sensory sensitivities. At the Beals Memorial Library, a sensory box containing headphones, chewies, sunglasses, fidgets, timers, and other items is included in every single program. To determine what to include in these boxes, staff worked with local schools. In addition to supporting neurodivergent youth’s participation in existing programs, these boxes allow patrons to test out sensory-friendly resources for free before deciding whether to independently purchase them. The library also makes “sensory checkout bags” available to patrons for in-home use.

Existing programs can also be modified in ways that promote greater awareness and acceptance of neurodivergence. At the Dodge Center Public Library in Dodge Center, MN, staff have adapted their storytime programs to include more books with neurodiverse characters. These programs now also include stimulation breaks, which give participants an opportunity to make use of the numerous sensory-friendly objects (sensory socks, a balance board, fidget devices, weighted blankets, etc.) staff added to their “library of things” in response to community feedback. Along similar lines, at the William B. Harlan Memorial Library in Tompkinsville, KY, staff not only purchased a variety of sensory-friendly items (including soft rugs, pillows, and noise cancelling headphones), but also set up tents for children “who don’t want to leave the area entirely but still need a safe zone — just for them — to view the action or play independently.”

As these examples suggest, making existing library programs more sensory-friendly also entails making library spaces more sensory-friendly. LTC grantees are doing this in a variety of ways. At the Boylston Public Library in Boylston, MA, a community conversation revealed the need for more quiet spaces—and for a reduction in visual stimuli. In response, staff worked to declutter their space, rearranging individual rooms and purchasing new furniture to create quiet “nooks” stocked with noise-canceling headphones and other sensory-friendly items

To give patrons with sensory sensitivities “a place to calm and settle,” staff at the Dodge Center Public Library in Dodge Center, MN, built a calming corner — a wooden structure with soundproof tiles that includes a soothing jellyfish lamp, weighted blankets, noise-canceling headphones, and fidget toys. Outside their building, staff also built an area with a rocking bench, green planters, and musical playground structures — all of which offer opportunities for auditory and bodily stimulation.

Designing New Programs

It is not always possible to modify existing programs in ways that meet the needs of patrons with sensory sensitivities. When these programs contain activities that are overstimulating or have the potential to attract unwanted public attention, it may be best to create parallel experiences specifically for this group.

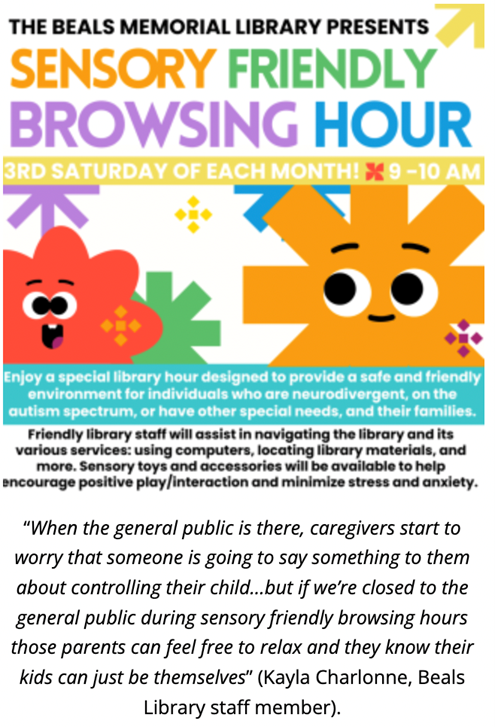

Perhaps one of the most straightforward options here is to create dedicated sensory-friendly library hours. The Beals Memorial Library regularly holds these outside of their normal hours. Doing so gives youth with ASD a chance to run laps, yell, or calm themselves in an extra quiet space. It also gives caregivers a chance to relax, as they need not worry about others’ reactions to their children.

Another idea is to create sensory-friendly story times. As staff at the Erving Public Library in Erving, MA explain it, the value of this program is that it gives children a chance to enjoy stories while playing and interacting with each other. Caregivers can participate “without worrying about whether their child can sit still.” At the Dodge Center Public Library in Dodge Center, MN, staff have created a sensory playtime that gives children a chance to explore different senses and textures while working on small and large motor skills. They also run a program called “Playdate at the Library” — an unstructured play time for children that also gives caregivers a chance to connect with each other and provide mutual support.

As a variation on this theme, once every month, the Beals library offers a sensory-friendly movie night. For this, the lights are only moderately dimmed, the volume is not as loud as usual, and rocker chairs are provided. Half way through, the movie is paused for an intermission that gives participants a chance to move freely about the library.

Some LTC libraries also hold gatherings that give neurodivergent patrons opportunities to socialize and build community. At the Erving Public Library in Erving, MA, staff host two socials every month: one in the morning that allows individuals in day programs to participate, and a second in the evening that allows families to participate. Each social includes an activity or a craft, a meal, and live music or a speaker.

New programs specifically designed for patrons with sensory sensitivities can also involve community partners. The Beals Memorial Library has created many experiences of this sort — including a sensory-friendly Santa visit! Working with their partners at the YMCA, staff host an open swim program specifically for individuals with ASD. Its goal is to give these individuals a chance to safely explore water, and to do so without having to worry about breaches of pool etiquette (for example, around splashing) that might otherwise cause disturbances. The event is open to all ages. Because transitions often take longer for individuals with ASD, it runs longer than the typical open swim session. And because these individuals are often unafraid of water, the event features double the number of lifeguards. The event has been a complete success. Parents who have struggled to get their children into a pool have been surprised at how readily they take to the water. And everyone always leaves smiling.

“Touch a Truck” was another of Beals’ popular programs for individuals with ASD. Held at the local American Legion’s parking lot (which is large and also fenced off), this program gave patrons an opportunity to explore different senses and textures by touching a variety of large vehicles — including a Jeep, a school bus, a mail truck, a fire truck, a logging truck, and an 18-wheeler. The program was facilitated by first responders, and included the use of special seat belt covers that helped raise awareness of how to interact with individuals with ASD (some of whom may be nonspeaking and/or sensory avoidant) in emergency situations. Through conversation about these special covers, first responders and caregivers learned that when involved in car crashes, people with ASD may be unaware of the danger they are in, may not respond, and may even resist or attempt to flee. This conversation helped assure caregivers that their children with ASD would be safe in the event of an accident even if they were unable to advocate for their children in the moment.

New programs can also be created for caregivers and community members more broadly. To give community members new communication tools, staff at the Beals Memorial Library run an ASL course through a local instructor who is deaf. At the William B. Harlan Memorial Library in Tompkinsville, KY, staff created an autism caregiver support group that meets monthly. This community-led project is one of the library’s “happiest accomplishments.”