Ask a programming librarian what a typical workday for them entails and you’re likely to get a long and varied list of tasks: meeting with partners, handling event logistics, working with budgets and creating marketing materials.

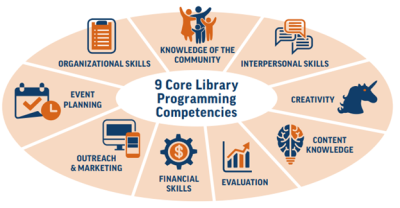

Research has shown just how varied a programming librarian’s skillset must be. In 2019, ALA identified nine areas of library programming competencies in its National Impact of Library Public Programs Assessment (NILPPA): Organizational Skills, Knowledge of the Community, Interpersonal Skills, Event Planning, Creativity, Content Knowledge, Outreach and Marketing, Financial Skills and Evaluation.

Given the increased emphasis on programming in the library field, ALA argued in the same 2019 study that it is increasingly important for library workers to receive training in these programming-related skills — including so-called “soft skills.” “Confidence in one’s ability to do programming appears to stem less from subject-area expertise (information skillsets) and more from the ability to leverage community resources and facilitate experiences (social skillsets),” the report stated.

Financial skills

Competency in financial skills is a must for information professionals. Programming librarians must be able to budget, seek funding for, and manage the finances of a program or suite of programs, often in collaboration with external partners, that is in alignment with the library’s priorities.

For the task force, four learning objectives stood out: futurecasting, the basics of organizational budgets, the specifics of program budgeting, and identifying external and/or additional resources.

To achieve proficiency, learners must have access to library practitioners and the financial documents and practices that guide them. Real organizational budgets with programmatic details are a must. Practitioners — brought in as guest speakers, perhaps — can provide the narrative experience accompanying those documents.

To make the learning stick, learners must have hands-on, practical experience with budgeting. In a professional development workshop, small groups of learners could work together to develop sample budgets; in a classroom setting, learners could develop case studies in small groups.

Just as a programming librarian uses financial skills throughout the day, in many contexts, the learning should be integrated into multiple projects. In the same way that technology is now baked into learning, the task force recommends that financial skills be woven into much of the professional development workshop-base and academic learning in library schools.

Evaluation

Programming librarians need to ensure that their programs are meeting the goals the library sets for them, and that they also meet the needs and expectations of those who participate. Evaluation tools also help ensure that we are spending time and resources wisely.

Because evaluation is central to most library activities, it can and should be taught to librarians, both in a classroom setting and as professional development; evaluation tools and skills change over time, so both methods of instruction can complement each other to help library professionals stay up to date in this area.

In a classroom setting, it is important for LIS students to become familiar with evaluation concepts such as backward design, which involves beginning all design from the end goals or outcomes and creating all lessons, assessments and evaluations so they point back to the goals. These skills can be scaffolded in a course, where students can begin by evaluating an existing program at their libraries to assess the goals and program design and offer suggestions for improvement based on the current data set and the theory they are learning in the classroom. A capstone project for this course could involve high-level assessment of evaluation for an entire library, or the development, implementation and assessment of a new program and evaluation at a library.

Creativity

Creativity is essential for library workers engaged in developing library programs. The need for new program formats — for example, for engaging local communities in democratic discourse, for mitigating consequences of social injustices, for countering misinformation, or for bridging societal divide — is evident, particularly in a time where both analog and digital programming has become an increasingly important part of libraries’ work.

To develop and design new programming formats and content in collaboration with stakeholders and community members and with a human-centered perspective, creativity and innovative thinking among library workers leading the processes is of the utmost essence. But how to teach it?

There are several methods and formats for teaching creativity in theory and practice. A particular format, design thinking, is gaining influence in several societal sectors and in iSchools and libraries as well. Design thinking is more than just a variety of methods; it is a mindset, a way of facilitating creative ideas and helping to get to the heart of what a design process really is trying to accomplish. It is an approach to problem solving that prioritizes empathy with and deeper understandings of users to define a problem; it actively engages in prototyping to develop solutions; and it iterates solutions through implementation and resulting modification. The short book “Design Thinking” by Rachel Ivy Clarke (ALA Neal-Schuman, 2020) provides a fine overview.

Hands-on projects like "The Wallet Project" can be used to teach the design thinking process. In the activity, students are first given three minutes to design (in this case, draw) the perfect wallet. While they don’t know it, this is a “false start”; the point is to show that the designer, by rushing into solution mode, hasn't done any effort in assessing needs of the user or empathizing or understanding the problem that the design is supposed to solve. The design is only based on what assumptions the designer might have had beforehand on what a wallet is supposed to do. As the activity progresses, the students work in pairs to design something useful and meaningful for their partners. The process entails asking lots of questions about their partners’ needs and wants for a wallet, listening, ideating, iterating based on feedback, and building a simple prototype.

How did you come to learn financial skills, evaluation and creativity? We invite you to join the conversation by sharing your thoughts in the comments below or by emailing publicprograms@ala.org.

Cindy Fesemyer is the Adult and Community Services Consultant for Public Library Development team at the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, Rolf Hapel is Affiliate Instructor at the Information School, University of Washington and Emily Mross is Business Librarian at Penn State University Libraries. Skills for 21st-Century Librarians: Task Force for the Development of a NILPPA-Informed Programming Librarian Curriculum was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services grant number RE-246421-OLS-20.

Read the next blog in the "Skills for 21st-Century Librarians series, "Local Networks: The Librarian Skills of Outreach and Marketing."