So how can libraries ensure that the language they’re using around disability is respectful and inclusive? The first and most important thing to note is that there is no single, universally agreed upon set of terms for referring to people with disabilities. Given that an estimated 1.3 billion people worldwide experience significant disability (that is, 16% of the global population, or about 1 out of every 6 people), this is not a surprising fact. Disability communities are rich, diverse, and complex, and the language we use to talk about disabilities should reflect this.

People living with disabilities identify themselves in different ways. Some use person-first language (i.e., person with a disability, person with autism), while others use identity-first language (i.e. disabled person, Deaf person, Autistic person). While there are no hard and fast rules around disability language, here are some best practices from disability advocates:

- Use the words “disabled” and “disability”;

- Refer to people as they refer to themselves;

- Avoid terms like “able-bodied” when describing people who do not have disabilities;

- Avoid deficit-based language; and

- Focus on disability accommodations and on how they improve access for all.

In what follows, we explore each of these practices, fleshing them out with examples from LTC libraries and showing how respectful, inclusive language can break down barriers that prevent people with disabilities from fully participating in society.

Use the Words “Disabled” and “Disability”

These are not bad words. Saying them shows you understand that disabled people are a protected class with rights. By contrast, phrases like “differently abled” may be seen as euphemistic — that is, as a way of avoiding discussion of disability. And the term “special needs” can stigmatize difference, because it suggests that people with disabilities are the only individuals who have unique needs. For more information and recommendations, see the recording and transcript of a 2023 webinar called “Disability is Not a Bad Word,” which was hosted by the ALA Social Responsibilities Round Table.

Refer to People as They Refer to Themselves

There are two primary ways of describing disability: person-first language (for example, “person with a disability” or “a person with autism”); identity-first language (for example, “disabled person,” or “an Autistic person”). Person-first language puts the emphasis on the individual, and underscores the fact that they are not defined by their disability. By contrast, those who see their disability as an inherent part of who they are generally use identity-first language to describe themselves. This language is often used as a demonstration of pride. But others find identity-first language to be dehumanizing.

Others prefer not to use the word “disability” at all when referring to themselves. People who have acquired disabilities through aging are particularly unlikely to identify as disabled. In many cases, other language may be appropriate here — for example, “individuals with mobility limitations,” or “people who use wheelchairs, walkers, or canes.” Provided they align with the way community members are already talking about themselves, these descriptors are perfectly permissible.

In other words: people self-identify in different ways. When it comes to disability language, the best approach is to proceed on a case-by-case basis, asking people how they’d like to be described and going from there. If you are unsure about what language to use, take your cue from the disabled person you’re speaking with. And when in doubt, the best option is to begin with person-first language.

Avoid Terms like “Able-Bodied”

When describing non-disabled people, avoid using terms such as “able-bodied,” “normal,” or “healthy.” These words present disability as something undesirable or wrong. Terms like “non-disabled” or “person without a disability” are much more appropriate. Another useful term is “people without visible disabilities,” as this underscores the fact that often, we can’t tell if someone has a disability just by observing their physical appearance.

Avoid Deficit-Based Language

Language that presents disabled people as lacking should be avoided. Outdated, condescending words such as “handicapped,” “crippled,” “impaired,” “special needs,” and “physically challenged” suggest that people with disabilities are somehow deficient. Similarly, phrases like “suffers from,” “is a victim of,” or “has been stricken with” present disability in purely negative terms — and as something that is pitiable. Disability is a normal part of the human experience, and having a disability does not make one incomplete. The language we use should reflect this.

Instead of the above phrases, use more neutral language, such as “he has low vision,” “she’s on the autism spectrum,” or “people living with bipolar disorder.” And instead of terms like “wheelchair-bound” (which presents disability as confining), use “wheelchair user” and “person who uses a wheelchair” — which are both more accurate and empowering. Accessibility devices like wheelchairs typically give users more freedom, and are not necessarily confining. As such, whenever possible, describe disabilities in ways that highlight what people can do.

Focus on Accommodations and Access

Disabled people require equal access. For this reason, it is always better to choose words that highlight the need for accessibility — for example, “accessible parking” — than the presence of a disability. And when discussing accommodations, highlight the positive impacts they have — not just for disabled individuals, but for all. Drawing attention to the generally beneficial impacts of efforts to make spaces, services, and programs more accessible to people with disabilities can help break down barriers and build support for such initiatives within the community.

Let’s Put it To Work!

The language we use to discuss disability is constantly changing, and no two disabled people are exactly alike. What some celebrate, others may completely reject. Given this, the best way to be inclusive is to refer to people as they refer to themselves. Achieving this requires ongoing conversations between library staff and users to understand individual identities. There is no single "right" way that works for everyone! As a result, across our group of LTC grantee libraries, you'll find a variety of ways disability and accessibility are being discussed—and that's exactly how it should be.

In addition to this recommendation, talking about disability in accurate, empowering ways means embracing the use of the terms “disabled” and “disability,” avoiding terms like “able-bodied” when describing those who are not disabled, using asset-based language that highlights things people can do, and highlighting the need for equal access and its positive impacts for all. By adhering to these general recommendations, libraries can promote the goal of disability inclusion and help create a world where the rights of people with disabilities are promoted, protected, and preserved.

Additional Resources

ALA’s Accessible Conversations Facilitation Guide can help you host library discussions with patrons with disabilities, to talk to them about the terms they use and how best to ensure they are included in library programs and services. Some other helpful resources include:

- Stanford University’s Disability Language Guide

- The ADA National Network’s Guidelines for Writing about People with Disabilities

- The National Center on Disability and Journalism’s Disability Language Style Guide

- Playcore’s Disability Language Tips & Examples

About this Article

This article was written by Knology – evaluator of the LTC Access initiative. The article is part of a series of blog posts exploring how libraries that received LTC Access funds are working to better meet the needs of patrons with disabilities.

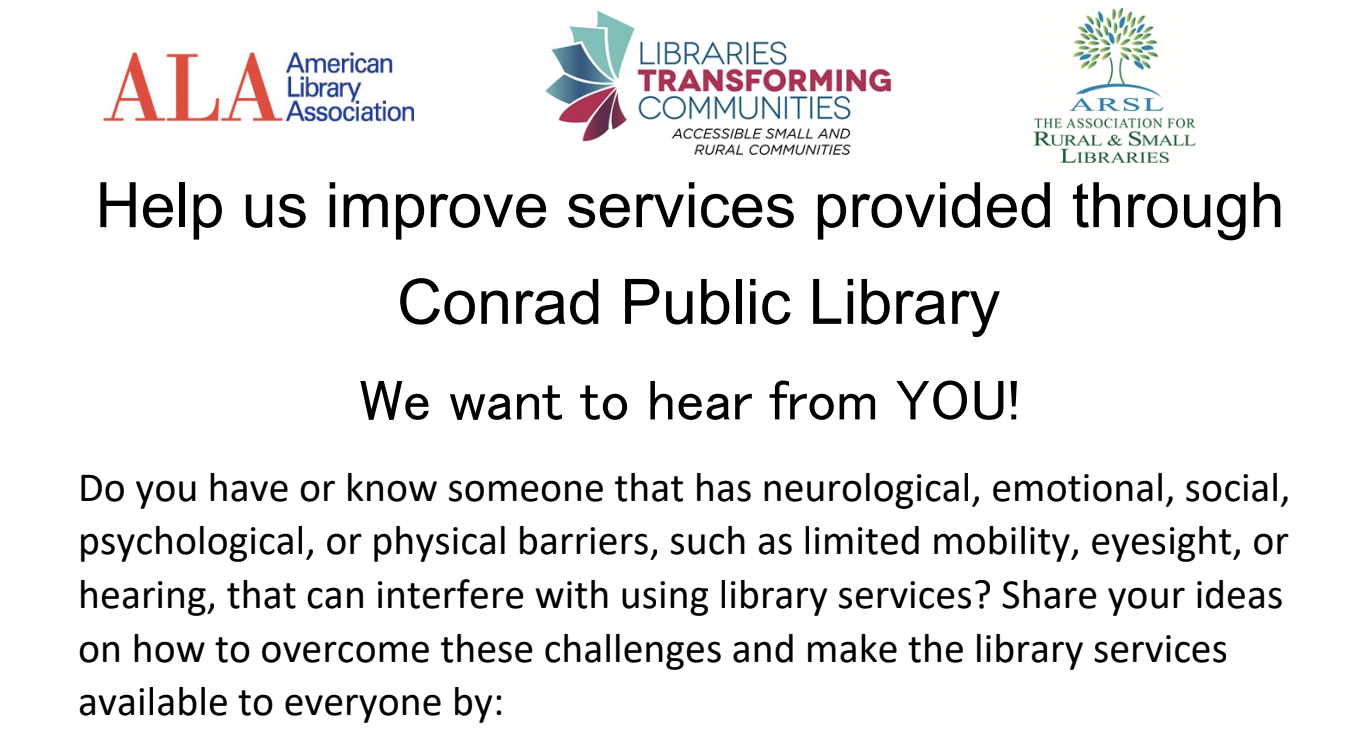

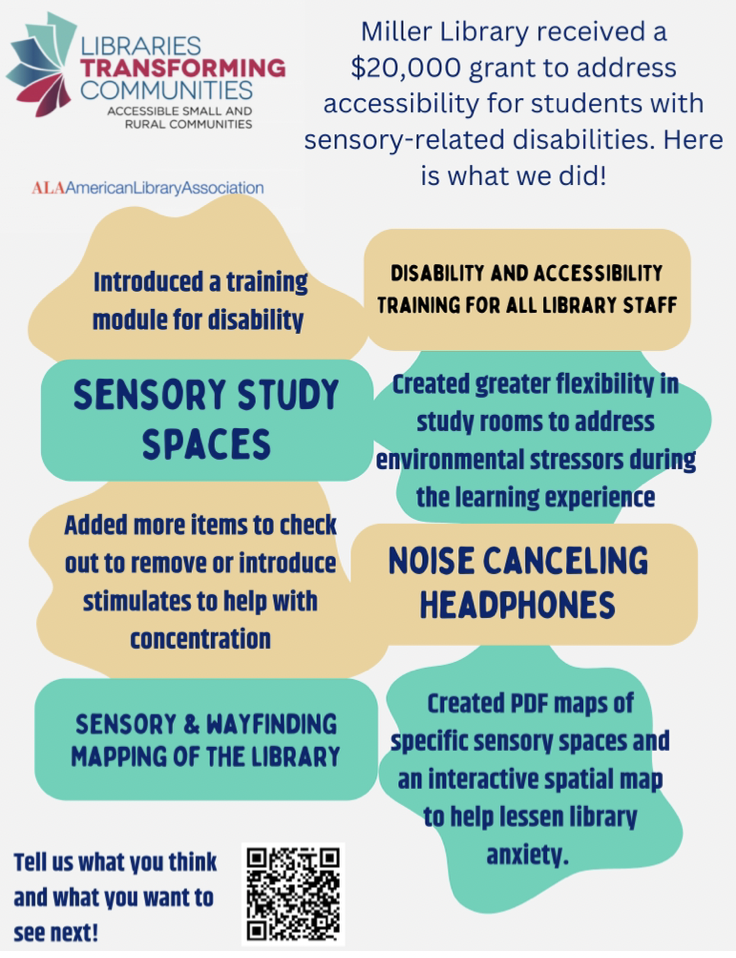

In other posts in this series, we provide a general overview of the accessibility projects these libraries have launched, look at attempts to put the disability rights movement’s ethic of “Nothing About Us Without Us” into practice, consider efforts focused on neurodivergent patrons and older adults, and look at how small and rural libraries are creating accessible community conversations. You can also read about how these libraries are overcoming challenges to planned accessibility upgrades, building partnerships to address community accessibility needs, and improving patrons’ experiences. And for stories of what individual libraries are doing, see the case studies we’ve published about the accessibility work going on at the Lee Public Library, Jessie E. McCully Memorial Library, and Beals Memorial Library.

For more on how libraries can become more accessible to patrons with disabilities, see the collection of resources we assembled.