In the library world, we often talk about how knowledge of the community is one of the most important, if not the most important, skill a librarian should have. If that’s the case, then who could be more knowledgeable than a librarian born and raised in the town they work in?

Jessi Baker was born and raised in Carterville, Illinois, a town of 5,000 people. She now works in her hometown’s library, the Anne West Lindsey District Library, as the adult and teen librarian. When the library was awarded an ALA Libraries Transforming Communities: Focus on Small & Rural grant earlier this year, she planned and hosted a community conversation for local teens.

Baker knows the community like the back of her hand. But at her first planned conversation program for teen patrons, she learned something new: the local schools don’t provide lunch during the summer break. As a result of this conversation, Baker used her librarian brain and strong local connections to help solve this problem.

I spoke with Baker about what the grant means to her community and how she has connected with local organizations to help feed local kids this summer.

How do you go about making connections with the community in your town?

It's been a learning process. My first experience with cold calling (on behalf of a library) was for the O’Fallon Public Library. O'Fallon, Illinois, is a significantly larger city than my hometown, and I did not know anyone in the community. That was when I learned about cultural etiquette in the professional world.

Small-town librarians often follow a different set of professional norms; what is considered professional behavior in a larger area could be considered impersonal behavior by a small-town patron. Alternatively, trying to make a personal connection upon meeting with someone from a larger area could be seen as unprofessional behavior.

I was born and raised in this town, as were several generations of my family. When I would reach out to folks, within our introductions there would inevitably be the question, “Who are you related to that I would know?” I am fortunate that our community is one that wants to be engaged; people want to connect on a personal level and help however they can. This made it easy to reach out to the organizations and people I wanted to connect with.

When I received the LTC grant, I started looking for organizations that specifically offered resources for teens, and then searched well-known community organizations to see if they provided services for this age demographic. For this conversation, I looked into resources such as mental health providers, homeless/youth shelters, food distribution centers or programs and after-school programs. While our conversations did have teen patrons, they were open to everyone in the community of all ages. I was focusing more on drawing in adults that were connected to teens to solve issues teens face.

You were required to host a conversation as part of your LTC grant. What was your conversation like?

Ten people attended our first conversation, and an additional five signed up to receive minutes but could not attend. Seating was limited due to COVID-19. Attendees included scout leaders, a local university professional, parents, high school students, M.I.G.H.T.Y. Moms members, library staff and the city community center coordinator.

We had a presentation by Lindsay Schroeder, a representative of the Night’s Shield in West Frankfort. This nonprofit organization is the only homeless shelter for youth within several hours' radius of our region. They provide a wide range of services and support targeted at teens, services the majority of the group did not realize they offered.

The topics we chose to discuss were teen needs: food insecurity and housing, as well as summer jobs and programs. We chose these topics for a variety of reasons. We were a few months from summer and wanted to ensure those in need had access to, and information about, local resources, especially since the pandemic had changed what a “normal” summer would look like for our small town. Many people wanted to know what programs would be available, modified or cancelled, and many groups wanted the opportunity to advertise their programming.

Weeks before the meeting, I confirmed the representatives I wanted to speak to the group and asked all attendees if they had anything they wanted to add to the conversation. I then built an agenda based on the topics we were going to discuss and included a question-and-answer portion after each presentation.

At the meeting, the council chose the next topic for discussion. While writing the agenda, I began to look for resources to include that teens may need for summer. This is when I discovered free lunch would not be provided to students over the summer, and I started looking at the number of students who received those lunches during the school year and known food distributions over the summer.

The LTC Leading Conversations in Small and Rural Libraries Facilitation Guide is a great free resource to start with if you are planning your own conversation programs.

After you found out that free lunch wouldn’t be provided to students over the summer, how did you organize community members to come together for food drives?

We have so many “knowledge keepers” in our town. They are people who know exactly where to find resources when you need them and will drop everything to assist others. But our knowledge keepers are busy people, and without them or a lack of availability, there is potential for a breakdown in connecting people with those resources. I thought if we put these representatives in the same room together, we could utilize everyone’s knowledge and resources to find a solution, or at the very least compile a schedule of known food drives.

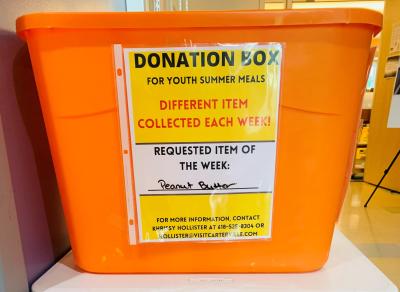

I can’t take full credit for organizing our food drive; I can only take credit for bringing the issue in front of the right people. We have an amazing community center coordinator, Khrissy Hollister. Khrissy is one of the ultimate knowledge keepers for the Tri-C area. She currently coordinates a food drive put on by the city and Gumdrops (a local organization). I knew it was crucial to include Khrissy in the conversation, and I was correct. Within 15 minutes of discussing the issue, she said, “We can definitely organize this. Do you want to work together?”

We needed research before we could host the conversation on food insecruity and housing, so I came up with a list of known resources for food insecruity and homelessness to add to the agenda. As a librarian in today’s world, you need to check the validity, mission and connections of each organization before inviting them to the conversation. Finding factual information from reputable sources was crucial in presenting this issue. By having quantifiable data from research, we were able to hit the ground running by knowing the exact number of people who needed help. Having knowledge of how databases are created and categorized was also important to this conversation; one of the goals is to create a database of resources gathered and shared by our members to be shared with the public.

What advice would you give to a librarian who discovers a problem in their community?

I believe it is our responsibility, as librarians, to be active members in our communities. Libraries are one of the few entities that see this diverse of a population, daily. We see problems firsthand, often because we are asked to solve them. To many, we are expected to be the knowledge keepers of our community. If we find an issue that has not been addressed, we need to bring attention to it!

I encourage librarians to be educated and proactive in issues their community members may face. Research the statistics for your area and compare them to available resources; this will quickly tell you if there is a need that is not being met. When investigating resources for a problem, it’s important to analyze how the problem began, as well as immediate and long-term solutions. This helps narrow the type of resources you are searching for.

Reach out to your knowledge keepers! Knowledge keepers are hidden everywhere: nonprofit organizations, school guidance counselors and administration, city employees, victim’s advocacy representatives at your local courthouse, universities or community colleges, free and low-income health care clinics, mental health professionals, scout leaders, ministerial alliances, and of course other local librarians are just some of the groups I would recommend reaching out to. You must think outside the box when deciding who to contact. They may not have the resource you need (right now), but they may also serve a population that has this need, and therefore they can connect you with the appropriate group.