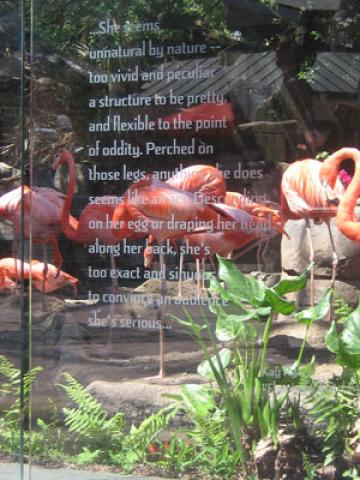

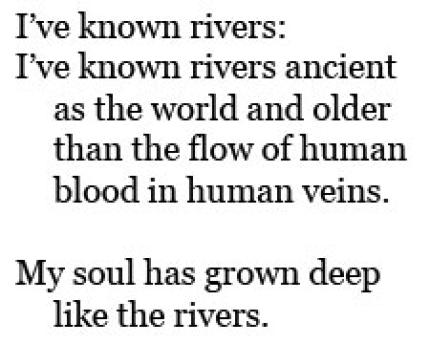

Visitors to five zoos around the country are experiencing the benefits of a unique partnership. In addition to encountering animals, they are also welcomed by poetry—the opening ofLangston Hughes’ “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” awaits them along the banks of the Trout River at the Jacksonville (Fla.) Zoo and Gardens, and an excerpt from Kay Ryan’s poem “Flamingo Watching” is etched onto the glass at the exhibit of these pink birds at the Audubon Zoo in New Orleans, for example, along with hundreds of others. Visitors in these cities also enjoy poetry, nature, and conservation-themed programs and displays at libraries. Programming at both the libraries and the zoos has featured a mix of both nationally known poets, including Sandra Alcosser in Brookfield, Illinois, and Mark Doty in New Orleans, and local-area poets, such as the two “Poetry by Candlelight” programs featuring Gina Ferrara and others at the Milton H. Latter Memorial Library in New Orleans.

Made possible with funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services, poets-in-residence Mark Doty, Joseph Bruchac, Alison Hawthorne Deming, and Pattiann Rogers, and project leader Sandra Alcosser collaborated with wildlife biologists and exhibit designers at five zoos and four public libraries around the country (New Orleans; Little Rock, Arkansas; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Jacksonville, Florida; and Brookfield, Illinois) to create exhibitions and programs that feature poems celebrating the natural world and connections between species. The zoo installations debuted in spring 2010, and library programming will continue through fall 2011. The American Library Association is collaborating with Poets House to share the outcomes of this multicity project at the ALA Annual Conference this June. A panel discussion, “The Language of Conservation: A Case Study in Library-Zoo Partnerships,” will feature representatives from Poets House, the New Orleans Public Library, the Audubon Zoo, and New Orleans poet-in-residence Mark Doty, who will later lead a tour of the zoo installation.

For some librarians, this was their first time collaborating with their local zoo. Everyone was eager to engage in the new venture and excited about the chance to work together to create new programming synergies. “The Language of Conservation Project finally gave us a chance to get together and do some things,” said Bettye Fowler Kerns, Associate Director of the Central Arkansas Library System.

Navigating the cultural differences between the public library world and zoos was difficult for some partnering organizations. Libraries are free for all, while zoos depend on paid admissions to support them. Accustomed to large crowds motivated by an interest in animals, zoos can draw audiences with relatively spontaneous programs, while libraries have to do more publicity and planning to bring together those with shared interests. Dealing with staff changes, particularly at libraries struggling during the economic downturn, has been challenging as well. However, a commitment to work together has paid dividends for both institutions. One zoo was able to retain a staff position because of its involvement in the Language of Conservation project. “There can be a large difference in the size of audience and approach for programming for the zoo and library,” one zoo official commented, but “there is no difference in the sincerity with which each organization works toward accomplishing their respective vision and mission.”

Libraries and zoos have worked together in various ways to encourage patrons to visit both institutions, from developing joint publicity and materials, to collaborating on programming appealing to all ages. Brookfield’s adult book discussion groups gathered to learn more about the project and chose conservation-related titles to read to youngsters making gym shoe gardens, and seventy adults braved a malfunctioning air conditioning system in New Orleans to attend “Indigenous and Endangered: An Evening of Louisiana Poetry” with Louisiana Poet Laureate Darrell Bourque and others. Representatives of both libraries and zoos also participated in press conferences for the poetry installations. Other examples of collaboration include:

1 All Jacksonville Public Library cardholders received discounted admission to the zoo.

2 Staff from the Milwaukee County Zoo and the Zoological Society of Milwaukee provided live animal programs for 316 children during the summer at thirteen branches of the Milwaukee Public Library. The zoo also created and printed five bookmarks with the catchphrase “See the animals and poetry at the Zoo; Read about the animals and poetry at the Library,” with images from the collection of animal prints in the library’s Krug Rare Books Room.

3 Central Arkansas Library featured zoo activities in their “Make a Splash” summer reading program and held the finale of the program at the zoo. They also offered free passes to the zoo for children in the summer reading program to ensure equitable access to the finale event.

4 The Chicago Zoological Society collaborated with Riverside Public Library to sponsor a poetry contest on project-related themes in which eighty-eight children participated, and designed poetry installations for display in the youth services area of the Riverside Library.

5 Andre Copeland, head of Interpretive Programs at the Brookfield Zoo, discussed North America’s iconic animal with twenty library visitors during his “Bison Paving the Way” presentation.

6 Both young people and adults gathered under the verse-filled leaves of the Jacksonville Library’s “Poet Tree” for children’s poet and author Richard Lewis.

Some participating libraries also felt that opportunity the collaboration presented for installations of conservation-related poetry and animal images had a transformative effect on the library’s atmosphere. Riverside Library director Janice F. Fisher, commented on the installation of the poetry as part of the Language of Conservation Project:

The project has created deep and lasting collaborative roots between the participating libraries and zoos, inspiring both sides to want to continue to work on conservation issues and integrate poetry into their future projects. “The library team is a great partner,” says J. J. Muelhausen of the Little Rock Zoo. “We have learned much from them and are happy to have an ongoing relationship with them.” Missy Abbot of the New Orleans’ Latter Library adds, “I’ve made friends with some of the people at the zoo, so we’ll be keeping in touch even after the program is officially over.”

A white paper including a bibliography/resource list; articles by poets in residence writing on the cannon of nature poetry; and ways to mediate the competing agendas of poets, librarians, scientists and zoo officials; as well as tip sheets on library programming, zoo installation design principals, and how to pick a poet for a place and evaluating your success are being developed for those wanting to learn more about the project and replicate the project in their location, and will be available at the ALA Annual Conference and as a downloadable PDF on the Poets House website by June.

Brookfield Public Library Director Kimberly Litland sums up the value of the Language of Conservation project to her community in this way:

We’re confident the partnership will increase our visitor’s awareness of how their daily actions impact the environment by way of the powerful verses on display at both the library and at the zoo. … The inspirational poetry plants a seed, perhaps even somewhat unconsciously, and hopefully will impact the thinking of each individual as they consider their part in the conservation equation.