Rural libraries have a special role to play in the communities they serve. In fact, the smaller the community, the bigger looms the library—although there are admittedly some pretty tiny libraries out there. It’s not so much the size of the collection, or number of staff members, or even how many hours a week the library is open. A library has a unique relationship with the people it serves. Now that we are in the digital age, the computers available for public use have become a cornerstone of the public library. The traditional collection of circulating books, the reference collection, even the magazines (remember the Readers Guide?), all take on a new and modern flavor when audio books, e-books, “googling” for information, and digital editions come into play. That old adage, “the more things change, the more they stay the same,” seems less true than it used to be. However, there is one thing that hasn’t changed: The public library can be, and often is, the focal point of learning and culture in the community. And the rural public library is uniquely situated to be exactly that.

Through weekly preschool story hours, early childhood literacy is advanced and emphasized as crucial to the development of reading skills in young children. Local groups—from political parties to reading clubs, from knitters to choral groups—reserve space in rural libraries for people to meet and engage their neighbors in civil discourse of the highest level. Exhibits of local artists grace the walls and display cases. And, most importantly, public programs are offered, like so many flowers “in the garden of earthly delights” that is the library. By offering programs that are free and open to the public, the library becomes that focal point.

Where Can I Find Funding?

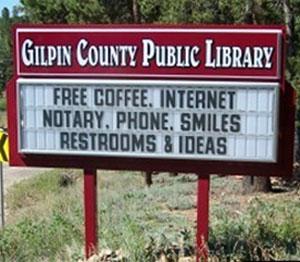

Your Friends of the Library can be your best friends when it comes to programming. You may be fortunate, with your library’s Friends already on board when it comes to funding programs. If that’s not the case, however, you can cultivate your relationship with them. At the Gilpin County Public Library in Black Hawk, Colorado, it was not an immediate union when I started about thirteen years ago. The Friends were (and are) a hard-working group of people who care passionately about the library and its programs. They raise money through book and bake sales, an annual Barnes & Noble Book Night, and membership dues and donations. A relationship of trust had to be established when I took over administration of the library as the new director.

It is fair to say that a certain pessimism about the potential of library programming existed. There was a history of low turnout for public programs. A few influential members of the Friends’ board were skeptical about the prospect of spending for programs, when it seemed to make more sense to concentrate on traditional needs, such as supplementing the book budget or purchasing computer hardware and software. Slowly, through some early programs and projects that met with success, the Friends began to trust my judgment. Once the public responded to programs, and the members of the Friends board found themselves as program participants, a confidence was born from little advances, and a partnership formed. They began to crave more fresh programming ideas, and I realized a new-found freedom to be creative. Once this symbiotic partnership was established, there was no telling what could be accomplished, and that’s when the fun began.

And don’t forget grants. There are program packages offered as grant awards by the American Library Association’s Public Programs Office, such as“Let’s Talk About It.” If you don’t think your little rural library can compete nationally for these programs, consider that the Gilpin County Public Library, which serves a county-wide population of only around 5,000, has received two “Let’s Talk About It” grants in the last four years. It is often the case that state humanities councils offer funding for public programming, so you might benefit from making contact with the council in your state to get on the mailing list for grant invitations and notification of deadlines. ALA and its Public Library Association division will also offer grant awards and invite proposals. Familiarize yourself with their websites and never underestimate your chances for success. There seems to be a trend in these grant opportunities toward more inclusiveness, especially when it comes to small and rural libraries.

What Kind of Programming Will Work in My Rural Library?

Poetry readings provide an outlet for the creative juices of the community. Film showings can afford a shared experience to a small group of people, who, immediately after viewing, are able to talk about what they just saw. And when you can get a local film critic or film buff to facilitate the discussion, it’s even better. Here’s a short list of some of the public programs we’ve been able to offer over the years that proved popular with the community and strengthened our relationship with our most important supporters, the Friends of the Gilpin County Library:

- We have had up to three five-part film series each year for the last ten years, with a noted film critic leading a discussion about each film (funded by the Friends of the Library).

- We are in our fifth year of having an Artist-in-Residence in the summer months: we've had a Poet-in-Residence, a Visual Artist-in-Residence, a Musician-in-Residence, a Theatrical Artist-in-Residence, and, in the summer of 2012, we’ll be having a Quilter-in-Residence (funded by the Friends of the Library).

- We were selected as one of only fifty pilot sites in America for the “Research Revolution” video viewing and discussion series, beginning in April 2003, sponsored by National Video Resources, the National Science Foundation, and the American Library Association (a large screen TV was purchased by the Friends of the Library).

- In 2008, we were selected as one of only thrity libraries in America for the “Let’s Talk About it: Love and Forgiveness” reading and discussion series, sponsored by the American Library Association and the Fetzer Institute for Peace.

- We were selected in 2011 as one of only sixty-five libraries in America for the “Let’s Talk About it: Making Sense of the American Civil War” reading and discussion series, sponsored by the American Library Association and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

- We alternate twice a year between A Midsummer Night’s Poetry Reading and A Midwinter Night’s Poetry Reading, which features local poets and offers an “open mic” to anyone else who wants to read (funded by the Friends of the Library).

- We purchased twenty-five fine art prints, representing some of the most famous paintings in art history, made possible by a generous grant from the Friends of the Library, and had them framed for exhibit whenever we are between shows by Gilpin County artists. This small collection of prints includes such artists as Gauguin, van Gogh, Matisse, Picasso, Monet, and Klee, and is very popular with library patrons.

- We received the EBSCO Award for Excellence in Small/Rural Public Library Service in 2010, based on the annual Artist-in-Residence program.

In addition to considering what kind of programming to offer, consider when to offer it. Just as the summer reading program for children is an annual occurrence in most public libraries, with a history of statistics and a future of hopes and dreams, other types of programming can also take on that sense of consistency from one year to the next. Our poetry programs mentioned above have become semi-annual, marking (roughly) the midsummer and midwinter dates on the calendar. The film series are three times a year, in the spring, fall, and winter. And the artist-in-residence program is planned in the spring and presented in the summer.

To say that these programs each gain a sort of life of their own, a certain momentum, is an understatement. By presenting any one of them, and allowing it to evolve and develop according to community interest and support, raises the bar for public programming in any given community. As expectancy grows, and the library meets it satisfactorily, so does community pride in the library and all of its services. People will begin to look from one summer to the next, from one film series to the next, and before you know it, a sense of tradition is established. That makes the library an integral part of life in the community, maybe even the focal point of learning and culture. Living in a community with a library that is active in public programming becomes a special place to be.