Every other week, Lucia Pieri writes poetry and discusses American literature with about 10 other immigrants at the Rochester (Mich.) Hills Public Library. For Pieri, the Newcomer’s Book Club not only builds friendships and perfects her English; it’s an intellectual opportunity that benefits women.

“Usually we come (to the United States) with our husbands, and our husbands have their jobs and their activities and they’re satisfied,” said Pieri, who moved from Italy five years ago. “Back home, [women] were employees somewhere. Here, you feel very un-useful sometimes. Here, you’re a housewife, and it was not your role. For a while it’s nice, but you feel very uncomfortable or sometimes depressed, so it’s nice to be involved with some activities that make your brain work.”

Last year, the number of immigrants in the United States hit a record high of 42.1 million, according to an analysis of Census Bureau data by the Center for Immigration Studies. The Census Bureau estimates this number will increase steadily over the next 45 years.

Many libraries are answering the population increase with “bridge programs,” programs that help immigrants integrate into their new communities. Below, five libraries share how they are welcoming immigrants and helping to break barriers for new Americans.

- Crossing borders with a book club (Rochester Hills Public Library)

- Legal advice at the library (Contra Costa County Library)

- Citzenship through conversations (Multnomah County Library)

- Historias para todo el mundo (Kern County Library)

- A market of newcomer resources (Flushing Library)

- Resources

Crossing borders with a book club

Longtimed educator Elana Izraeli, Ph.D., was nearing retirement when she was asked to facilitate a book club for immigrants at her local Rochester Hills Public Library. Now, more than 10 years later, Izraeli has witnessed blooming friendships, literacy triumphs and unwavering dedication within her Newcomer’s Book Club.

Rochester Hills Public Library was one of the first libraries in Michigan to offer English-language learning book clubs, according to Michelle Wisniewski, head of the library’s Oakland Talking Book Service, who works with Izraeli to lead the program. The Newcomer’s Book Club meets on Thursdays from 10 to 11:30 a.m. to discuss poetry, American short stories and the news.

Attendance ranges from 10 to 20 participants, most of whom are highly educated women. Since its founding a decade ago, the club has welcomed participants from an array of countries, including France, Japan, Cuba and China. Generally, participants have strong English language skills.

The group discusses American writers that some members have never heard of before coming to the States, such as Frost, Angelou, Kipling and Dickens. Sometime the group doesn’t even get through one paragraph because they “are deep into discussion, and everyone’s bringing his or her background knowledge,” Izraeli said.

The club also explores skills beyond reading. For U.S. holidays, members bring in home-cooked dishes to discuss their cultural significance. Members also write poems that are bound into books that they can take home.

“Every opportunity I have to make them express themselves and talk and present, I use it,” said Izraeli, who had also facilitated an immigrant book club at West Bloomfield Township (Mich.) Public Library.

One rule of the book club is that no one corrects another person’s pronunciation. Izraeli, who’s trilingual, said her focus is making the members feel comfortable reading aloud.

Newcomer’s is a tight-knit group. Pieri, a member for two years, said the book club has fostered friendships and expanded her awareness of other cultures.

“It’s very easy to have friends because all of us are foreigners, and we need to know each other,” said Pieri. “There are people all over the world, and in other situations, you wouldn’t have the opportunity to talk and to learn.”

The club doesn’t meet in the summer because many members visit their home countries, but that doesn’t stop them from learning.

“I remember the moment toward the end of the year when I told them that June would be the last meeting of the year,” said Izraeli, “and several of them came to me and asked if we could continue and do it in one of their houses.”

Izraeli said it’s important for an immigration book club to be managed by a library staff member who is completely committed to the program. For Izraeli, Wisniewski is that person. Wisniewski is in charge of planning, scheduling, marketing and participating in sessions, along with printing and distributing copies of each literary work.

“[My library career] has included public programming as well as driving a 26-foot bookmobile through ice and snow. The ELL groups have been one of my most rewarding work experiences,” said Wisniewski. “I have traveled around the world without leaving the library.”

Legal advice at the library

“If my parents are green card holders and apply for my immigration, will I be able to stay in the United States?”

“Can I leave the country while my application is pending?”

“What do I do if my landlord is threatening to report me?”

Librarians are no stranger to urgent questions, but legal advice might be pushing their job description.

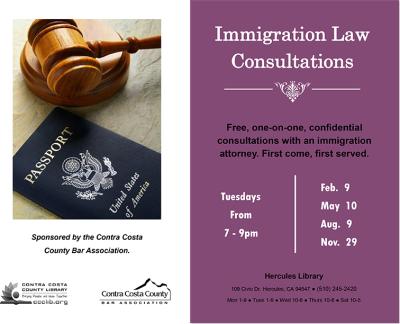

Contra Costa County (Calif.) Library partnered with a local bar association to provide free one-on-one sessions with volunteer immigration lawyers in the evenings. Adriana Nino, the adult and teen librarian at the Pleasant Hill library branch, said the program is a stepping stone for patrons.

“They might not know where to start when it comes to dealing with lawyers or legal issues, or what steps in the process they should be preparing for,” said Nino. “This event offers them a free and confidential opportunity to get all their basic questions answered.”

These questions might increase with the Supreme Court’s recent deadlock on President Obama’s immigration reform. The justices split 4-4 on the president’s plan that could have helped as many as 5 million undocumented immigrants avoid deportation.

Anywhere from 2 to 12 patrons attend each two-hour program. Before the session, the library requests participants fill out a waiver form provided by the Contra Costa County Bar Association (CCCBA). Right now, the sessions are sporadically scheduled at different branch locations. But with an immigration section added to the association this year, CCCBA Education and Programs Coordinator Anne Wolf said her long-term goal is to schedule regular workshops in libraries that need them.

Wolf advises librarians who want to offer this type of program to be upfront with a potential partner.

“I appreciate it when [librarians] reach out to me and say, ‘Look, I have people coming in and asking for these things. Could you work with me to set something up?’”

Once the partnership is in place, Wolf explained the program is a collaborative process: She contacts volunteers, and the library provides the space and coordinates the clients on the day of the program. In the end, Wolf said, librarians know whether an immigration workshop is right for their libraries.

“They know what their patrons want,” said Wolf.

Citizenship through conversations

Nooshirvan Rose moved to the United States from Iran in 2012. He finds it difficult to speak English, so he borrows books and DVDs from the local library. His most rewarding learning approach is attending Talk Time sessions at Multnomah County Library in Portland, Ore.

Talk Time is a weekly conversation circle for immigrants to practice English. Lisa Regimbal, the library’s adult literacy coordinator, said the sessions are “free-form” — participants talk about their daily lives or topics such as local politics. Sometimes members bring in confusing articles or sentences to review. The one rule: during Talk Time, everyone speaks English.

“Usually people have enough to participate in a conversation without too much trouble,” said Regimbal. “If anyone has a challenge, we use bilingual dictionaries or we use picture dictionaries.”

Oregon has a high immigration population, with one in 10 residents being foreign-born, according to ImmigrationPolicy.org. One Talk Time session might bring together people from Iran, Iraq, China, Colombia and Japan. Rose, who has attended Talk Time regularly for the past three years, said many people discuss their own cultures at the sessions.

“I can improve my English,” said Rose. “I can improve my hearing, listening and talking to people.”

Anyone can drop in for the Talk Time program. The number of attendees range from 3 to 17 people, depending on which of the five branches hosts it.

Regimbal said some of the Talk Time materials are borrowed from Tacoma Community House, a Washington State multi-service center for immigrants and refugees.

In conjunction with Talk Time, Multnomah County Library also hosts citizenship classes, six-session series that prepare immigrants for their citizenship interview with U.S. history and government exams. Regimbal said the library started offering the sessions at least 10 years ago.

“People were asking for them,” said Regimbal. “Even though other organizations do the classes, we do a lot of ours on Sundays at times when there weren’t other classes.”

There remains a high demand. The library fits as many participants as the branches’ conference rooms can hold, and the registration-only sessions usually fill up. The library hosts about 11 citizenship courses a year at four rotating branches.

Most of the two-hour sessions are taught by library volunteers, but the library has also partnered with local organizations, such as SOAR and Mission Citizen.

Library staff publicized the program at outreach events and contacted community colleges to help promote it. They made it clear the sessions were open to everybody — whether they have a library card or not.

Historias para todo el mundo (Stories for everyone)

“Hola, cómo están todos? Hello, everyone. How’s everyone doing? Welcome to today’s storytime.”

That’s how Kern County Library (Bakersfield, Calif.) Branch Supervisor Rafael Moreno begins his bilingual storytime videos on YouTube. His video “La Paloma de Mo Willems,” which incorporates puppetry and summer reading promotions into storytelling, has more than 200 views.

The library started the YouTube bilingual series a year and a half ago because of the library’s rural location. Kern County is the third largest county in California. Although the system has 24 branches, many rural communities are still too far from library resources, Moreno said.

“The good things about it is that we’re able to go out and reach out to people all over, not just here in this county, but anybody who watches it,” said Moreno. “It’s available 24/7; parents can show it to their kids in the store, while they’re traveling in the car. It gives us a virtual connection with the community.”

In conjunction with its storytime videos, the library also has a dial-a-story service; parents can call a number to hear a bilingual story. (If you want to listen to dial-a-story, check out this calendar that lists the phone number.)

On Fridays at 10 a.m., Moreno also hosts bilingual storytimes at library branches. One of the program’s benefits is its connection with non-English speakers “who probably felt like the library didn’t have any programs available to them,” he said.

Bilingual storytime isn’t just for the children; it’s for parents, too.

“It gives the opportunity to model storytime for parents who want to read to their children at home,” said Moreno.

Spanish storytimes reach Hispanic immigrants, who greatly appreciate library services, according to a 2013 Pew Research Center report. The study also states Hispanic immigrants are more likely than other groups to say the closing of their local library would have a major impact on their families.

When Maria Villafuerte-Campbell moved to the United States at 11, she was bullied in middle school for speaking differently; her local library became her go-to place to learn. Now, she brings her son Mateo, 3, and newborn daughter Emilia to the Kern County storytimes.

“I have so many great memories when I hear a story or song that I learned as a child. I want to share that with my children,” said Villafuerte-Campbell. “I want them to grow up bilingual or trilingual if possible. I want them to be proud of their heritage and to embrace the language their mother grew up with so that we can share experiences en español.”

Villafuerte-Campbell learned of the program two years ago from the library’s calendar when she was checking out books for Mateo. Moreno said he also publicizes the program and its specific themes with bilingual email blasts. For libraries who don’t have a bilingual librarian to organize and publicize the program, Moreno suggests reaching out to teachers who can volunteer during the summer.

Villafuerte-Campbell says Moreno’s reading techniques and outgoing personality have impacted her son’s education.

“Mateo knows [Moreno] well and has a smile on his face when we encounter him in the community,” said Villafuerte-Campbell. “I also find Mateo singing songs in Spanish at home, and this always warms my heart because I know that taking him to this program is making a difference in his learning.”

A market of newcomer resources

Ten miles from the Statue of Liberty — with its “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free” plaque — stands the Flushing Library, the host of the widely successful annual Immigration Resource Fair in New York’s Queens borough.

New York is known as a melting pot; between 2011 and 2014, Queens borough alone gained 75,000 new immigrants, according to the New York Daily News. In 2014, Immigrant Advancement Matters, a nonprofit that supports immigration bridge programs, proposed the fair idea in a Queens borough Immigration Task Force meeting. The library is just one of the immigrant service providers present at the bimonthly meeting.

With much support and planning from the Queens borough President’s Office, the Flushing Library utilizes all three floors to host educational workshops, cultural performances and 35 organizations and government agencies.

At last year’s four-and-a-half-hour June fair, around 700 people gathered for workshops on how to navigate the education system, Hispanic and Chinese performances, on-site legal clinic services and municipal ID sign-ups. The library offered translation services in Bengali, Chinese, Korean and Spanish. This year’s fair, which will be held in October, is planned to offer the same services and programs.

Cathy Chen, the assistant director of programming and operations of the library’s New Americans Program, explained that choosing partners is the first step of planning.

“You need to get politicians or elected officials involved to support you because they have the influence and they can advocate for this,” she said. “During last year we had a panel of different officials discussing immigrant integration into society; that’s the really important issue to bring up.”

Besides providing equipment and organizing the presentations, the library was also charged with promoting the program. To get the media involved, the library held a press conference, where program partners detailed the services immigrants could find at the fair.

The team decided the Flushing Library was the perfect place to host the event because it’s a “go-to place for immigrants” and “one of the leading models to serve immigrants,” Chen said.

Resources

Read more about successful library-led programs for immigrants by visiting the following program pages:

- The American Place, Hartford (Conn.) Public Library

- New Americans Project, Denver (Colo.) Public Library

- New Immigrants Project, Austin (Texas) Public Library

Learn more about your community's immigrant population by exploring the following resources:

- U.S. immigration by state, Migration Policy Institute

- Popular destinations for U.S. immigrants, Business Insider

- U.S. immigrant gateway cities, Governing.com