In response to this growing need, community-based initiatives for people living with dementia and their caregivers are becoming more and more common. Along with museums and other cultural institutions, in recent years, libraries have increased their efforts to address these patrons’ unique needs. Through Memory Cafés, speakers’ series, and other programs, libraries are reducing the social isolation that often comes with a diagnosis of dementia, offering people with dementia and their carers new opportunities for support, connection, and empowerment. In addition to enhancing health and well-being, these programs are countering some of the stigmas and stereotypes that prevent people with dementia from leading full lives, improving public attitudes toward dementia and in the process helping build more dementia-friendly communities.

But the process of becoming dementia-friendly goes beyond individual library programs. At its core, a dementia-friendly community is one that enables people with dementia to “live their pre-diagnosis lives for as long as possible.” Promoting the dignity and autonomy of people with dementia, these communities create the conditions by which people with dementia can continue accessing local services and amenities. As Jessica Fairbanks of Dementia Friendly Vinton notes, people with dementia “still want to come out in the community. They want to go grocery shopping, they want to go to the pharmacy, they need to pay their insurance bills.” By giving them the tools and supports needed to do these things confidently and safely, dementia-friendly communities help people with dementia exercise choice and self-control in daily life. They make it possible for people with dementia to “remain independent or live in their home with support for as long as possible.”

Libraries can contribute to the broader project of building dementia-friendly communities. As the evaluator of ALA’s LTC: Accessible Small & Rural Communities grant, we’ve seen how the Vinton (Iowa) Public Library is making progress toward this goal. Based on our evaluation of the library’s Memory Café program, in what follows, we outline some simple steps your library can take to become a dementia-friendly space.

Pursue Dementia-Friendly Training

The first step to becoming a dementia-friendly library is to simply learn more about dementia and its impacts. Organizations like Dementia Friends USA offer free online training, but in-person interactive training is also available in many communities. The goals of this training are twofold. As Kathy Good of the Chris & Suzy DeWolf Family Innovation Center for Aging & Dementia explains it, participants first acquire a knowledge of “dementia basics” – for example, the fact that while people with dementia experience declining cognitive abilities, “their feeling state probably increases,” making them more adept at “reading your body language and responding.” The training Fairbanks offers at Dementia Friendly Vinton uses embodied learning to help participants understand what it’s like to live with dementia. As part of the training, Fairbanks has participants put on gloves, glasses, and headphones, and then attempt to complete a series of tasks — for example, making a cup of coffee, or picking up a book to read. These exercises, she explains, help guide participants “to have a little more empathy and understanding of their interactions with someone living with dementia.”

This is the second goal of dementia-friendly training. In addition to learning more about the disability, participants learn how to respectfully and empathetically engage with people with dementia and their care partners. A caregiver who participates in the Vinton Public Library’s Memory Café notes that while people with dementia “want to be liked and want to connect with people,” many people “aren't all that interested or patient." Fear of “uncomfortable or awkward situations,” Fairbanks adds, can prevent people from engaging with or reaching out to people with dementia. Dementia-friendly training reduces this fear, helping participants become more successful in their interactions with people with dementia by helping them see the person rather than the disability. As Good puts it, being a friend to someone with dementia is about recognizing that “the person is still there” – that even if they do not interact in the same way others do, “they still can [communicate].”

By helping participants recognize the signs of dementia and master techniques for effectively helping those in need, training can promote the social inclusion of people with dementia. This is especially important, Fairbanks notes, given the fact that prevailing stigmas around dementia often make it “very hard for [people with dementia] to ask for help.” Highlighting the benefits of the training she received, Vinton library assistant Lisa Hopkins says that her participation gave her “a different perspective” on dementia, helping her to “just slow down and be present for each individual out there.”

Create a Dementia-Friendly Space

A key part of being dementia-friendly is making the built environments people with dementia encounter accessible. As dementia progresses, those living with this disability become more dependent on their environments to support their autonomy. By ensuring that their facilities are designed in ways that take account the changes in perception, awareness, mobility, and communication that accompany dementia, libraries can create spaces that are welcoming and safe for people with dementia.

Above all else, dementia-friendly spaces prioritize safety and ease of navigation. As is the case for those with mobility disabilities, people with dementia benefit from the use of simple layouts, uncluttered decor, assistive furniture, wide aisles, and other design elements that assist wayfinding. Spaces that have intuitive or obvious uses are ideal, and as a general rule, it is best to reduce the need for decision-making by enhancing visual access to possible destinations (for example, by limiting the number of doors in an area). When this is impossible, placing signs with large, easy-to-read text at decision points (for example, bathroom exits that indicate how to return to the library) can be helpful, as can other environmental cues. In particular, glass doors should be clearly marked as entrances/exits. Ensuring that restrooms have enough space for a patron who needs assistance to be accompanied by a caregiver is also vital. Finally, libraries can also avoid unhelpful stimulation by concealing entryways to potentially harmful areas.

Many of the design features that make spaces more accessible to patrons with sensory sensitivities also benefit people with dementia. For example, by setting up quiet spaces with seating where someone can relax if they become anxious or confused, libraries can help people with dementia regain a sense of calm. On a more general level, reducing the amount of background noise and prioritizing the creation of low stimulus environments can make libraries more dementia-friendly spaces.

Another important consideration is visual contrast. Many individuals with dementia experience decreasing contrast sensitivity — that is, the ability to detect boundaries between objects. By making use of contrasting colors, textures, and lighting, libraries can establish supportive environments that markedly improve the experiences of people with dementia. Contrasting colors do not always make environments more dementia friendly, however. As an example of how these contrasts can lead to potentially harmful misperceptions, Fairbanks explains that when very dark rugs are placed on more lightly colored floors, they “can look like a hole to someone living with dementia.” In this case, the goal should be to ensure that the color of the rug matches that of the floor. For the same reason, consistent lighting is better than bright lights and dark shadows.

Improving Collections

Building up a collection of dementia-friendly books, media, and other materials can be incredibly beneficial for people with dementia and their caregivers — and for other patrons interested in learning more about the disability. When thinking about developing such a collection, it’s important to actively involve those with first- and second-hand experiences of dementia in the acquisition process, as their concerns, needs, and interests should drive the kinds of materials that become part of this collection. Indeed, content creation is one way to establish and deepen relationships with this patron group. In addition to developing a patron-driven acquisition plan, look to develop a mixed-media collection, as having a variety of materials (printed books, audiobooks, music, films, etc.) can spark “different kinds of mental engagement and even resilience.”

For many people with dementia, the ability to recognize pictures persists longer than the ability to comprehend purely text-based materials. Because of this, illustrated texts and other visually engaging resources are an essential part of any dementia-friendly library collection. In recent years, a number of publishers have begun creating visual materials for people with dementia — including Pictures to Share and Shadow Box Press.

Nonfiction books are also incredibly valuable for people with dementia. Books that contain scientific and medical information about dementia can build awareness of the disability’s impacts on health and wellbeing, while memoirs can offer a sense of how to navigate dementia from a clinical, interpersonal, and social standpoint. Biographies and other books about history are helpful on account of their ability to spark readers’ memories and provoke conversations about their own pasts. Nonfiction materials for people with dementia and their caregivers can also include guides listing resources in the community (support groups, respite care, healthcare providers, etc.) and online.

Music is another important part of any dementia-friendly collection. Research indicates that music is a powerful tool for working through emotional and cognitive challenges associated with dementia. Hearing familiar pieces or songs offers another means of connecting with the past, and these musical memories can bring psychological, social, and emotional benefits.

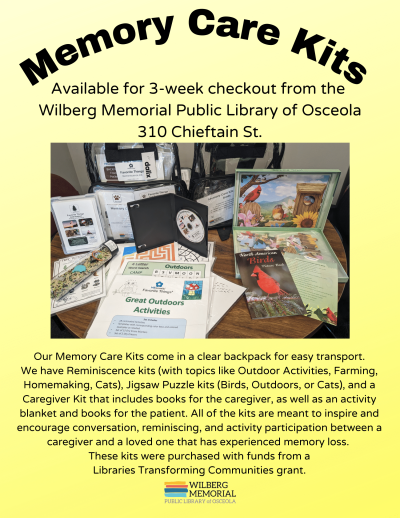

Working with people with dementia and community partners, libraries can also create memory kits — that is, collections of memory-triggering objects. These can include books, photographs, slideshows and other visual materials, recordings (for example, CDs, DVDs, and cassette tapes), and various tactile items (including cards, games, pins, and toys). Typically, these kits are organized by theme — for example, seasons, decades, different geographical locations, etc.

When adding new materials to a collection, attaching dementia-friendly tags and labels to them will ensure that they’re accessible to those audiences most interested in them.

Additional Resources

For more information on how to become a dementia-friendly space, the following materials will likely prove beneficial:

• Dementia Friendly America’s downloadable resources for many types of community organizations, including libraries.

• The American Library Association’s resources on library services for patrons with dementia, which are curated by the association’s Library Services to Dementia / Alzheimer’s Interest Group.

About this Article

This article was written by Knology and Kelly Henkle, director of the Vinton Public Library. It is part of a series of blog posts exploring how libraries that received funds through ALA's LTC: Accessible Small and Rural Communities are working to better meet the needs of patrons with disabilities.

In other posts in this series, we look at attempts to put the disability rights movement’s ethic of “Nothing About Us Without Us” into practice, consider efforts focused on neurodivergent patrons and older adults, and look at how small and rural libraries are creating accessible community conversations. You can also read about how these libraries are overcoming challenges to planned accessibility upgrades, building partnerships to address community accessibility needs, and improving patrons’ experiences. Other blogs in this series offer guidance on how to create sensory-friendly programs, how to talk about disability, and how to incorporate accessibility into library strategic planning.

For stories of what individual libraries are doing, see the case studies we’ve published about the accessibility work going on at the Lee Public Library, Jessie E. McCully Memorial Library, Beals Memorial Library, and Bixby Memorial Free Library.

For more on how libraries can become more accessible to patrons with disabilities, see the collection of resources we assembled. And for more information about LTC, see our historical overview of this initiative.